Few things are as hotly debated in deer hunting as the best caliber for the job, and in my area, that usually comes down to two classic calibers, .30-30 vs .308. Caliber choice matters little compared to deer shot placement, but still – choices matter.

Table of Contents

Putting Venison in the Freezer

The cost for everything is soaring. Trips to the grocery store are scheduled to minimize consumption of fuel, shelves are a never-ending source of sticker shock and beef, a basic staple, has assumed luxury status.

Which got me to thinking about November. Near as I can figure, based on a few recent queries about suitable hunting rifles, some shoppers are coming to the realization that deer are made out of meat. If that’s true, there will likely be an uptick in this fall’s hunting license sales.

One kicker though: Groceries aren’t cheap, but neither are new firearms. Which begs the question of whether a new gun is actually cost effective. Short-term, probably not. Beyond a gun, there’s gear, licensing requirements and the requisite skills. So much for instant savings.

Then again, some folks have hunted in the past or have close connections to those that still do, in which case a new firearm may not be necessary. It might not be the latest hot-rock long-range rifle, but it could still be up to the job. If it’s been around for a while, it could be a .30-30 lever-action, possibly produced by Winchester or Marlin. Here’s why…

.30-30 Past and Present

The first World War was fought with bolt-actions, but lever-actions were still outselling them by a 10:1 margin into the 1930s. Case in point, the Winchester Model 1894: During its lengthy run, Winchester produced over 7 million! Marlin, it’s chief lever-action rival, sold another 3 ½ million in evolutions culminating as the Model 336.

Popular calibers included the .32 Winchester Special, .35 Remington (Marlin) and .30-30 Winchester. But the vast majority were the latter, so it’s safe to assume there are still plenty languishing in household gun chests or closets – not to mention the “used” racks of gun shops.

That’s a plus regarding ammunition since, unlike other calibers (both past and present), factory .30-30 cartridges remain available – a classic example of supply and demand!

Over the course of its lengthy life, the .30-30 has been adapted to single-shots, pumps, and bolt-actions, but its home has always been lever-actions. Initially introduced as the .30 Winchester Center Fire (.30 WCF) for Winchester’s Model 94, it was the first (along with the .25 WCF) American cartridge to use smokeless powder. At that time performance was quantified by caliber (.308) and powder charge (30 grains), hence the .30-30 designation – from Marlin, no less.

As originally designed, the Winchester M-94 ejected spent cartridges through the top of its receiver – a poor choice for a scope. The Marlin M-336 has always featured a side-ejecting action with a solid-topped receiver, but it wasn’t factory drilled & tapped for scope bases until 1956 – the same era that ushered in a series of flatter-shooting calibers – to include the .308 Winchester.

But for decades prior, the preferred aiming system was a set of iron sights, relating to firearms of that era. Rimmed cartridges fed better through tubular magazines, and “round-nosed” (RN) bullets were required to prevent recoil-induced detonation of other cartridges. Not those blunt bullets were of much concern to woods-wise hunters for whom the .30-30 was a proven deer slayer.

Most shots occurred well within 100 yards (still true today in my area) where aerodynamic pointed “spitzers” offered no great advantages.

.30-30 Through the 20th Century

When it first appeared, the .30-30 drove “light” 160-grain bullets to around 2,000 feet-per-second (fps). But for many decades since, the common .30-30 offerings have evolved to 150 or 170-grain versions, the former approaching 2350 fps from a handy 20 ½” carbine. The result of the modern .30-30 cartridge is a useful balance of power to size, which has probably taken more deer than any other caliber – absent a fuss over exotic bullets.

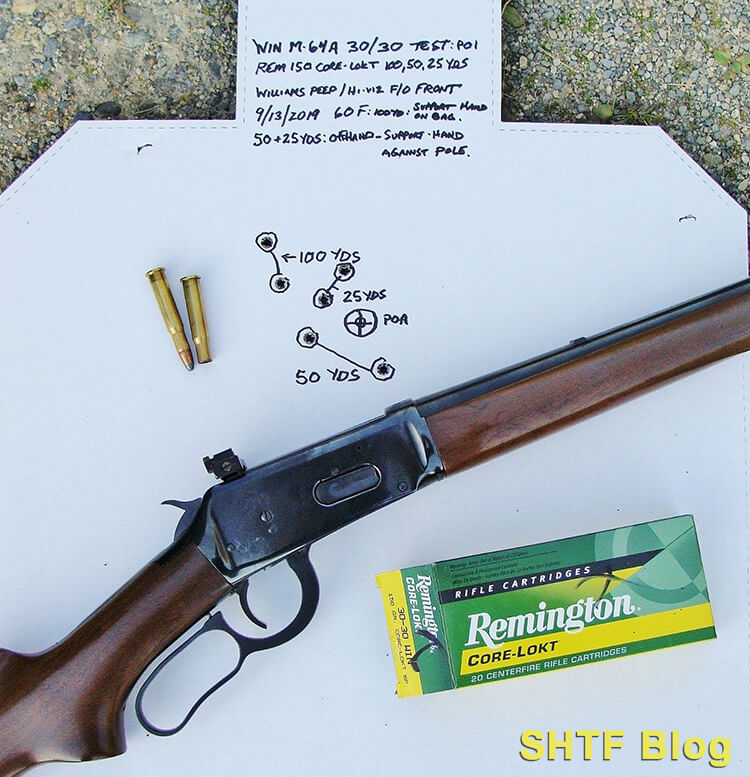

Like most folks who roam the woods with .30-30s, I just shoot basic factory RN loads and call it good. My particular thirty-thirty is a circa 1970s Winchester Model 64-A; a pistol-grip version of the ’94, with a longer 24” barrel. It easily puts three Remington 150-grain Core-Lokts into two inches at 100 yards using a Williams receiver sight and large green fiber-optic front element – a not-too precise, but entirely useful aiming system for the woods.

I’ve shot this combination at steel combat silhouette targets from 200 yards off DIY shooting sticks, and by using a slightly high chest-hold, five shots will smack the “chest” dead-on while producing fist-sized groups. Fun and easily doable – on that target. But it’s larger and shaped differently than a deer. The load is up to the job, but the sights would make precise shot placement difficult at that distance.

Remington’s 150-grain Core Lokts clock 2350 fps from the muzzle of my 24” Winchester. But how about other loads? Hornady’s American Whitetail line includes a 150-grain RN Interlock, listed with a MV of 2390 fps. According to their data, when zeroed at 100 yards it’ll strike 7.7” low at 200 yards – pretty close to what I see with Core-Lokts.

FYI, those in my hunting circle have had good luck with 150-grain .30 Interlocks on deer (as spitzer versions). Hornady lists this load as suitable for medium-size game up to 300 lbs. – with an emphasis on deer.

Basic 150 – 170-grain round-nose loads having been filling game poles for decades, and they’ll still work well within reasonable distances – ranges suitable for iron sights.

Recent .30-30 Developments

Nowadays, more shooters are probably familiar with optics than iron sights. Thus, later in its life, Winchester updated the M-94 to an Angle-Eject version that could accept a standard 3-9X scope. But, because Marlin was always the better host, far more are scope equipped.

If your .30-30 happens to have a scope, a switch to Hornady’s LEVERevolution loads could extend its hunting range to 200 yards – if they’ll feed through its tubular magazine.

Their streamlined Flex-Tip bullets are topped with compressible plastic tips so they fly like spitzers (but may hang up in some earlier followers). They’re also rated for game up to 1500 lbs., covering deer through moose and, of course, black bears. The Monoflex versions, being made from solid copper, are much tougher than typical jacketed lead bullets, combining reliable expansion with deep penetration.

The 140-grain Monoflex is listed with a 2465 MV, and it’s down 5.8” at 200 yards (when zeroed at 100 yards).

Moving to the jacketed 160 FTX version, advertised with a 2400 fps MV, if zeroed at 200 yards, you’ll be 3” high at 100 yards.

These loads ratchet the .30-30 up to a whole new level and could cover many hunting situations – assuming the rifle has what it takes to deliver. However, the above velocities were wrung out of 24-inch barrels and the vast majority of .30-30s are shorter carbines that’ll give up some speed. And aiming systems can impose further limits.

Optical Hurdles

Most thirty-thirties are designed for open sights so, even when equipped with scopes, their stocks are usually too low to provide solid cheek-welds – preferred for delivery of accurate shots. However, a clever small optical compromise is offered by Turnbull Restoration, and it could help those of us with older eyes:

As for me, I’m sticking with my weatherproof peep-sight system, more suitable for distances inside 125 yards – close enough to continue using basic RN loads like Core-Lokts, etc.

Rise of the .308 Winchester

After World War Two, the military began working on a shorter but still capable version of the .30/06 for use in a new generation of firearms. These efforts lead to the 7.62×51 NATO and the parallel introduction of a civilian version in 1952 – the .308 Winchester.

This cartridge was deemed to have great potential for use in civilian short-action rifles and it’s safe to state the .308 Winchester exceeded all expectations.

Velocities with 150 to 165-grain bullets aren’t far behind the ’06, which puts the .308 in an entirely different league than the .30-30. The original T-65 147-grain military load supposedly reached 2800 fps – the same velocity Hornady lists for their 150-grain .308 American Whitetail load (a great choice for deer). Their souped-up 150-grain Superformance version can supposedly reach 3000 fps, however, barrel length must be considered.

From my heavy-barreled 20-inch Remington Model 700 bolt-action, a couple slightly heavier 168-grain “tactical” loads clock closer to 2600 fps. Still, that’s probably at least 300 fps faster than souped-up 160-grain .30-30 Hornady LEVERevolutions fired through a 20 ½” carbine. The .308 wins speed contests because it’s designed to work at greater pressures than the .30-30 and its older ever-action hosts.

The .308 is also intrinsically accurate. Partial credit goes to its hosts which include a number of bolt-actions capable of one-moa (or better) accuracy – 5 shots inside an inch at 100 yards. The cartridge also hits the performance sweet spot of “good” ballistics without excessive recoil.

Common loads include everything from zippy 110-grain varmint offerings through 200-grain heavy-hitters, but the .308 really hits its stride with 150 to 180-grain bullets. Basic jacketed soft-points (like Remington’s Core-Lokts and Hornady Interlocks) will handle deer. A switch to the latest solid copper monolithics sold by Barnes, Hornady (and others) will cover larger animals through moose.

To put the performance of the .30-30 vs .308 into perspective, I zero .308s at 200 yards (+2” at 100 yards/- 9” at 300 yards). Steel silhouettes are routinely shot to 600 yards, or beyond if space permits – doable with the .30-30 but far from easy. Some recent fast-stepping calibers shoot flatter, but the .308 can still reach beyond 1000 yards with the latest 190-grain low-drag bullets – possible thanks to today’s rangefinders, ballistic apps, and scopes.

Moving in the other direction, “low-recoil” loads are available; useful choices for younger or recoil-sensitive shooters. Ballistically, they’re pretty much .30-30s – still useful enough to cover many hunting situations.

Bottom line: If you have access to a .308, you’re in pretty good shape.

.30-30 vs .308 – Starting from Scratch

If only one centerfire rifle was in the cards, I’d personally go with a .30-06. Ammunition is widely distributed, and it can do everything the .308 can while beating it with heavier bullets – at the expense of a longer action.

But many of us could do as well with a .308. It has the power to handle most North American game species and, because it’s such a popular caliber, ammunition is easy to find; and there are lots of useful loads to choose from. Even if using plain-Jane offerings in a lightweight sporter, the .308 has the reach to cover a quarter mile (or further) in the hands of a practiced shooter.

To exploit this cartridge’s full potential, it really deserves a scope. Those interested in a general-purpose rifle could do a whole lot worse than a moderate-sized 3-9X featuring quality internals and lenses. To gain a wider field of view while shedding a few ounces, there’s nothing wrong with a 2-7X. Today, the trend is toward fatter 30 mm scopes, but a 1-inch main-tube version will still cover most hunting situations without feeling top-heavy.

To simplify scope mounting and wring out the .308’s full accuracy potential, a bolt-action is hard to beat. Just about every version produced to date is drilled and tapped to accept scope mounts, and nearly all are also stocked correctly for this purpose. But due to the .308’s ongoing popularity, it has also been produced in all common actions to include single-shots, pump-guns, and lever-actions.

If you’re bound by tradition to one of the latter, it’ll feed by necessity from a box-magazine – not in the least a bad thing. Beyond used .308 lever guns (Winchester M-88s, Savage M-99s, etc.), there’s the current-production Browning BLR and Henry Long Ranger, both of which feature detachable magazines and ambidextrous operation. Before snatching one up though, mount it while considering the stock’s height relative to a scope.

Last Thoughts

If you can lay your hands on a serviceable .30-30, no worries. You’ll still be well-equipped to fill a freezer – especially one east of the big river. Most offer a means to add a receiver sight, offering more precision than a set of open sights. You may need a taller front sight; in which case a bright fiber-optic version will be advantageous during low-light conditions or bad weather.

Or, maybe, own ‘em both. Use the .30-30 for close shots or bad weather and the scoped .308 for everything else. If nothing else, a second gun is darned good insurance should some mishap occur. Could be a nasty fall, or some fiasco of greater magnitude, leading to greater concerns about availability of ammunition.

Since the above calibers are among the more common, assuming the quarry is deer-sized, you can get by with standard loads and stock up whenever it appears on-sale. I spied a few boxes in both calibers during a recent trip to a general store. They were a bit pricey, but they were available. Yes, there are more exotic calibers, and some can really perform.

The 6.5 Creedmore is “in” and the .30 PRC can trounce the .308 – but neither were on-hand. That’s probably just as well because if they had been, prices would’ve been astronomical.

Sometimes the KISS approach offers the greatest peace of mind.

Want to compare the .308 to another classic cartridge? Check out .223 vs .308.