Given the seemingly constant ammo shortage facing shooters and gun owners, hard-to-find bulk ammo deals, and growing frustration with ammo prices, it leaves many people considering reloading. If you’re an avid skeet shooter or waterfowl hunter, you might be wondering – is reloading shotgun shells worth it?

Short answer: Reloading shotgun shells requires some upfront costs, but if you have enough time and enjoy the process, you can save money by reloading your own.

Table of Contents

Ammo Shortages and High Prices

During a recent trip to a well-known hunting and fishing emporium, I stumbled into a lengthy line of customers in a corner of the gun department. The attraction turned out to be the morning’s meager shipment of ammunition, set out for rationed distributions from a small table. Nearby, the ammo isles were stripped bare of everything but a few oddball calibers. The whole scene was eerily reminiscent of a Soviet-era food market. BUT, I did find some bags of shotgun wads lurking at the rear of a shelf!

These types of shortages make the prepper ammo approach of buy it cheap and stack it deep difficult to achieve.

Through 2019, some “gun club” type shotgun shells were affordable enough to pretty much nix reloading due to the rising costs of components. But, early 2021 found me rummaging through my aging stash of primers, wads, shot, and powder. I was light on wads but, fortunately, the retail outing solved that problem. The other key component, shotgun shells, turned out to be a non-issue thanks to hundreds of once-fired Winchester AA hulls dutifully tossed into plastic bags. Items accumulating cobwebs suddenly had great value. It was time to dust off the reloading gear.

What do You Need for Reloading Shotgun Shells?

Reloading shotgun shells really begins with reliable data, followed by a suitable collection of empty shotgun shells. The necessary components (determined by the data) include a loading manual, shells, primers, powder, wads, shot, and reloading press. These items can be used to remanufacture a serviceable shell if a reloading press is available – or, maybe, even without one!

Looking for reloading supplies? Visit Brownell’s, Cabella’s, Optics Planet, or Sportsman’s Guide. Prices and availability vary, so always compare costs.

First Concern, Safety! Anyone capable of safe power tool operation should have what it takes to reload. The same general rules apply, including use of safety glasses. Common sense goes a long way. That, and safe data!

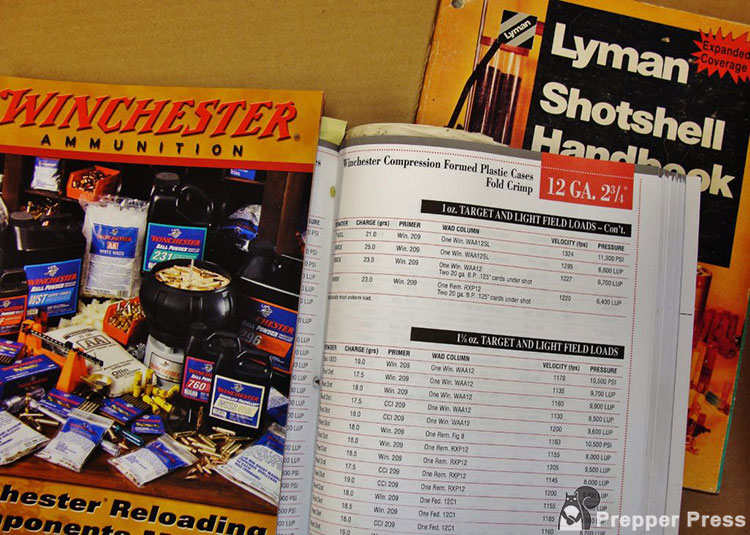

A Loading Manual

Shotgun shells operate at lower pressures than most metallic cartridges, but you can still get in a heap of trouble without reliable recipes which must be followed to the letter. Even a simple primer substitution can be dangerous. I often refer to the Lyman Shotshell Handbook (now in its 5th edition), which has lots of pressure-tested loads; sometimes dozens from one shell type. A manual is the logical first step which can help steer you toward compatible components – assuming you can find ‘em. The Lyman manual also contains in-depth coverage of the entire reloading process.

Shells

Most of today’s hulls employ a metal base and plastic body sealed with a folded crimp. Although they can often be reloaded, many aren’t worth the effort. Shotgunners gravitate toward the better target loads because they’re marketed as such; often providing six or more reloads.

Like many other shotgunners, I use Winchester AAs built via a “compression formed” process. Their eight-petal crimps won’t shed pieces like “poly-formed” six-petal types. The brass bases also resize well (many others are actually plated steel). That said, most buckshot shells are six-petal. They’ll work with large pellets but those with melt-sealed central crimps (Winchester) can leak small shot through the resulting gap.

Primers

Sometimes known as “battery cups,” these jumbo-sized primers ignite the powder through a blow from a firing pin. The 12 gauge Winchester AA hulls shown here will be re-primed using Winchester’s popular 209s, which will also work in smaller gauges down through .410-bore. See Winchester ammunition components.

Powder

One type can’t cover everything but, unlike many rifle propellants, some shotgun powders have further potential for metallic cartridges. Alliant’s Unique has long been used for handgun loads and it’s also my go-to 20 gauge choice. I’ve been using Alliant Red Dot in 12 Ga. target loads for decades, so that’s what you’ll see here – dispensed as specified by the manual. For safety’s sake, you’ll also need a basic reloading scale. Powder charges are quantified by weight in “grains” (not to be confused with kernels). I installed a bushing in the charge-bar of my press to meter 18.2 grains of Red Dot, verified by the scale.

Wads

Until the 1960s most wads were stubby fiber plugs or cards. Today, they’re plastic pistons with integral cups that contain the shot pellets. Most younger folks have probably never seen the early types, although they can still work in a pinch. In fact, you can even make them for peanuts using craft supplies (more to follow below). But, especially with plastic wads, the right combinations are necessary.

Beyond pressure concerns, they’ll need to fit within the shells. Using Winchester’s wads as an example, several types are sold to accommodate various propellant and shot combinations. A good manual has done the homework regarding pressure testing – and also proper fit. Those shown here are WAA12s designed for moderate 12 gauge target loads containing 1 1/8 ounces of shot. My press is adjusted to seat them firmly with around 45 lbs. of force (set via its built-in indicator).

Shot

Pellets come in different sizes from buckshot (the largest) to birdshot. Until the 1980s most were lead but, today, “non-toxic” alloy pellets are required for waterfowl. The cheapest alternative to lead is steel shot, often used in larger sized pellets (BB, #2 – #4) for ducks and geese. Some folks reload steel (or more exotic tungsten-alloy shot) using special components, but most of us still reload lead, typically with smaller (#7 ½, #8, or #9) pellets for clay target sports. FYI, a higher numbered pellet is smaller. Buckshot or slugs can also be reloaded although the latter normally require a special roll-crimp.

Caution: Don’t use steel airgun BBs! Those shown in the picture above are actually copper-plated lead #6s.

Reloading Press

Think reloading shotguns shells requires a reloading press? Ideally, but I started reloading at the age of 14 without any press at all. Instead, I used a basic Lee Loader hand kit. The process was tedious but the kit was simple and portable. It also worked surprisingly well.

Press-Free Methods

Sadly, the Lee kit has been discontinued. However, there are a few alternatives which can be seen on YouTube. The first is as basic you can get, requiring little more than a nail and dowel!

Or, for a relatively minor $85 investment, there’s the X Ring USA hand-tool system, not all that different from the Lee design. It would be a great survival-type addition that could fit almost anywhere.

No wads? Well, you can even make your own…

Reloading Presses

Several companies manufacture shotshell presses. Prices vary, for the most part commensurate with their output. Probably, the most affordable and widely distributed presses are sold by Lee Precision and MEC Outdoors.

Lee Precision Lee is still selling affordable but well-proven Load All presses. Although largely made from plastic, they continue to get good reviews. No doubt, they see much good use by weekend tailgate shooters:

Higher-end presses are sold by Hornady Manufacturing, Dillon Precision, Ponsness Warren. These presses are more substantial and geared for larger-scale production. Prices run from around $575 to $1500 (up), but no one will complain about their quality:

- 366 Auto™ – Hornady Manufacturing, Inc

- SL900 Shotshell Reloader

- Duomatic 375 (12/20ga.) – Ponsness/Warren

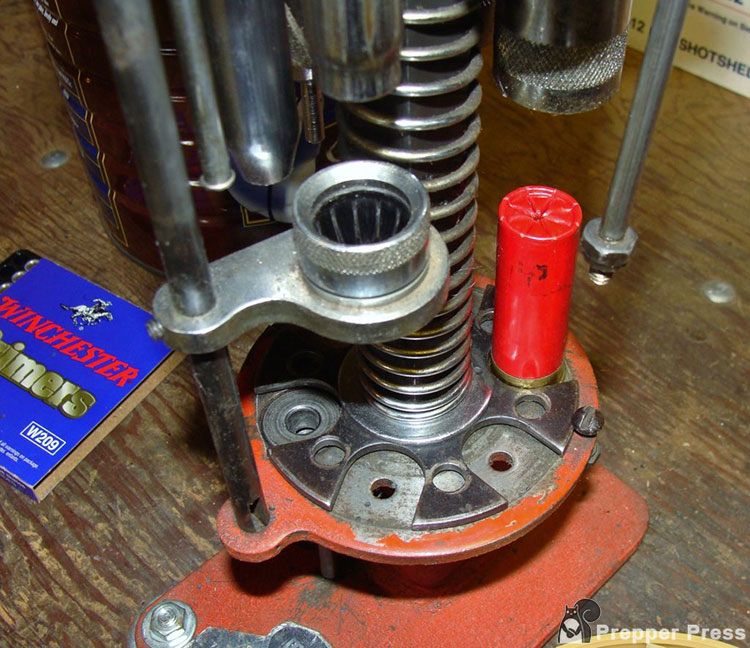

MEC Outdoors The three presses pictured are MECs, a brand that’s been in widespread use forever and a day. They offer a number of models to meet most needs without busting budgets. Those you’ll see here include a basic MEC 600 Jr. and higher-output MEC 650s. MEC also sells some pricier models with extra features, some of which permit upgrades to their basic presses.

Press Function

The star of this show, my 12 gauge MEC 650 Progressive Press, was purchased at a lawn sale sometime in the early 1970s! The automatic priming system was missing but the $25 price was right and it still cranks out shells just fine (I manually insert the primers). This was a great way to get into reloading shotgun shells with minimal investment.

Later, I added a 20 gauge MEC 650 which works the same way. Powder and shot are dispensed from two plastic bottles, and metered through a reciprocating charge bar. A series of resizing, charging, and crimping dies below are aligned with a six-position, rotating shell plate (or holder).

Each press of the handle forces the die assembly downward over the shells to perform the various steps while activating the charge bar though a linkage.

An empty shell is manually inserted from the 9:00 slot, advancing as the shell-plate is indexed (manually) counter-clockwise.

Eventually, it’ll reemerge at 9:00 as a ready-to-shoot shotgun shell. Once everything is working properly the choreographed steps will result in a machine full of shells in various stages of completion – including one finished shell per handle-stroke. But, of course, there’s a learning curve. And, even veteran reloaders can experience an annoying deluge of stray powder or scattered pellets caused by operator error. That said, once a rhythm is established, shells can be cranked out in large quantities.

Because I shoot fewer .410 shells, they’re loaded on a basic MEC 600 Jr. Each is reloaded one at a time and manually repositioned to undergo each step. The charge bar is also manually cycled, but there’s much less to go wrong. Of course, the production rate is slower, but a 600 Jr. should do the job for many weekend claybird shooters.

Shell Production

To better illustrate the reloading process, I manually fed shells through my progressive 12 gauge MEC 650 in a manner similar to the simpler MEC 600 Jr. The steps are pretty much the same though regardless of your method. Let’s take a trip around the press, rotating the plate and pulling the handle to perform each task:

Step #1: De-priming Step #2: Re-priming and powder charge

Step #3: New wad and shot charge Step #4: Initial crimp

Step #5: Final Crimp Step #6: Final resize and finish

Step #1 (9:00) The fired primer is punched out on the downstroke.

Step #2 A new primer is seated (it’ll be fed automatically with a fully functional 650). Upon full downstroke, the charge bar shuttles to the right, dropping a charge of powder into the shell.

Step #3 A new wad is seated (positioned manually above the shell). At full downstroke, the charge-bar will shuttle left again, depositing a load of shot into the wad.

Step #4 Initiates partial crimping.

Step #5 Final crimp.

Step #6 Final resizing and finishing.

The loaded shell is removed when it reappears at 9:00 so the process can continue. My simpler .410 MEC 600 Jr. would’ve better illustrated the steps, but I opted to kill two birds with one stone, gaining a further advantage: Sometimes, you can build what you can’t buy…

Custom Loads

Turned out I was running low on a 12 gauge target-type hunting load created for a lightweight over & under field gun. Setting it apart, the payload is 1 1/8 oz. of hard copper-plated #6s. I use it for pheasants as the first shot. At around 1150 fps, recoil is mild and improved-cylinder patterns are excellent. Any misses will permit a quick recovery for a more potent following load from the tighter-choked barrel.

Trouble is, this mild load of #6s is pretty much non-existent in factory form. Since a couple boxes will cover two seasons, I used them to illustrate the various reloading steps.

Resizing Insurance

This load could see further use in a semiauto, so I added an additional step. Prior to their actual reloading, I ran each shell through my MEC Super Sizer. This tool is a separate press of sorts with powerful steel fingers, designed to squeeze metal shotshell bases back to factory specs. Although unnecessary with most double-guns or pumps, it can improve semiauto function. MEC’s Sizemaster-series reloading presses incorporate this feature.

So is Reloading Shotgun Shells Worth it?

What if you don’t have components or equipment? Well, at this point, I view the acquisition of components more like buying silver and keep a watchful eye for any items of value. A stash of fired shells makes a good start, so save what you shoot. Spring for a manual and you’ll have a useful guide for further acquisitions.

Surprisingly, I’ve seen some reloading presses online, along with a smattering of components. Primers of all kinds are scarce and expensive. Wads are sketchy. Shot is hard to find, although I did recently find 10 lbs. of expensive copper-plated #6s for $32; enough to create 140 of the above reloads.

Pricing of primers, wads, and powder (often out-of-stock) yielded a per-shell cost of about 37 cents for my higher-end copper-shot load, or $9.25 per box of 25 – still expensive, but less than any similar factory offerings. Of that, each 1 1/8 oz. shell used 23 cents-worth of shot. The cost for primers and wads is fairly consistent regardless of the gauge.

Because shot is the most expensive component, with claybirds on the horizon, I switched my 12 gauge charge bars to build a lighter 1 oz. load of lead #8s. This shot is cheaper, and sold in 25 lb. bags currently priced at $51; enough for 400 shells. Assuming my math is correct, per-shell shot cost will decrease by 10 cents. The per-box cost should be around $6.75. Actually, I was shocked to see a price this high. Then again, the other day, I spotted two lonely off-brand boxes of 12 gauge #9 target shells priced $9.50 for each!

The above Winchester AA-equivalent reloads cost a third less – without a mask. Lighter loads or smaller gauges can yield more savings, especially with shipping factored in. A 20 Ga. 7/8-ounce uses less shot and powder. Normally pricy 2 ½-inch .410 target shells use just ½-oz. of shot! Result: Cheap shells!

As for components and equipment, the latter sometimes languish unrecognized among items gun shop “used” displays. And, good weather means yard sales! When the original owner passes on, much of this “stuff” becomes just that, available for a song.

The buddy system is another possibility. Shooters eventually network and some either reload, or did so in the past. Joining a club that offers claybird sports can open additional doors since the members sometimes join forces to make bulk purchases for significant savings. That makes reloading shotgun shells even more attractive.

Truthfully, attaching a price to anything ammo-related is difficult at the moment. It’s pretty much catch as catch-can with no end in sight. The solution? Adapt, overcome – and maybe, accumulate some reloading essentials.