Shotguns for homesteads go back as far as shotguns themselves. They are the most versatile, all purpose firearm up to meeting the varied tasks that come with owning a homestead, and nothing beats simplicity like a single-shot shotgun.

A Brief History of Shotguns on the Range

Believe it or not, “the gun that won the west” was not a Winchester Model 1873 lever-action rifle. The pioneers that ventured across the prairie packed all sorts of commodities in their wagons. So, for the most part, a firearm was just another implement, a tool no different than any other tool. To that end, the most affordable type was some type of shotgun domestically manufactured with Industrial Age machinery.

Many 19th century European double-barreled shotguns were guild guns, built using cottage-industries that specialized in locks, stocks, or barrels. The final product involved much hand-fitting so cost was relatively high, although still less than those from prestigious London shops. Demand for either was more limited since hunting was an upper-class affair conducted on large estates where price was of less concern.

Meanwhile, the situation in America was the opposite with a huge demand for firearms, driven by adventurous folks seeking homesteading opportunities on the plains. Catalogs were soon full of more affordable machine-made guns including many with a pair of smoothbore barrels. These 10 or 12 gauge double-guns were a whole lot better than no gun, and they offered great versatility.

Subsistence hunting was a given, nicely covered by smaller shot loads that could fill the family pot with everything from rabbits to sage grouse. Larger quarry like deer could be harvested with buckshot or, sometimes, “pumpkin balls.” Either load also provided an effective defensive capability as long as ranges weren’t too extreme; inside around 40 paces.

A rifle was sometimes added to handle longer-range targets but, on a day-to-day basis, the shotgun was the mainstay family choice that could be pointed instead of aimed. This was true in 1880 and it still is today.

The Basic Homestead Shotgun

In keeping with a no-frills approach, the affordable shotgun option is some sort of basic, break-action, single-shot. Peruse most gun shops and you’ll spot such a gun languishing in the “used” rack for little cost. Good chance it’ll be branded Harrington and Richardson or New England Arms, both of which came from the same now-defunct factory.

Other manufacturers offer similar single-shots, although most are imports that come and go raising concerns about service and spare parts.

Meanwhile Savage reentered this market with a line of Chinese-built guns. Their 12, 20 gauge, and .410-bore Stevens Model 301s retail for around $200, complete with replaceable choke tubes.

Henry recently jumped in with a nice line of higher-end break-barrel guns sold with interchangeable chokes, priced accordingly at around $500. Importers hawk other inexpensive guns but a used, domestically-built H&R (sold in various gauges including 28) may cost less. This is despite gun buying frenzies that emptied inventories of other more glitzy types.

Many of these simple guns still lean in doorways or barns, on standby to repel unwelcome critters from corn-raiding racoons to crows. Activation of a small tab or lever will allow the barrel to tilt downward, exposing the breech for loading.

An external hammer is common to most. When drawn fully to the rear (cocked) the gun will be ready to fire. A few have separate safety levers, although they should all be un-cocked with caution. Some have auto-ejectors that spit out a fired shell as the action is opened, while others provide partial extraction.

There’s a good chance the gun can be easily disassembled by unsnapping its forend, freeing the barrel for removal. If so, reattachment of the forend to the separated barrel will result in a handy two-piece takedown package. Weight is usually minimal, but that does raise concerns about recoil – especially with heavier loads (a 10 gauge should be horrendous).

More About Gauges

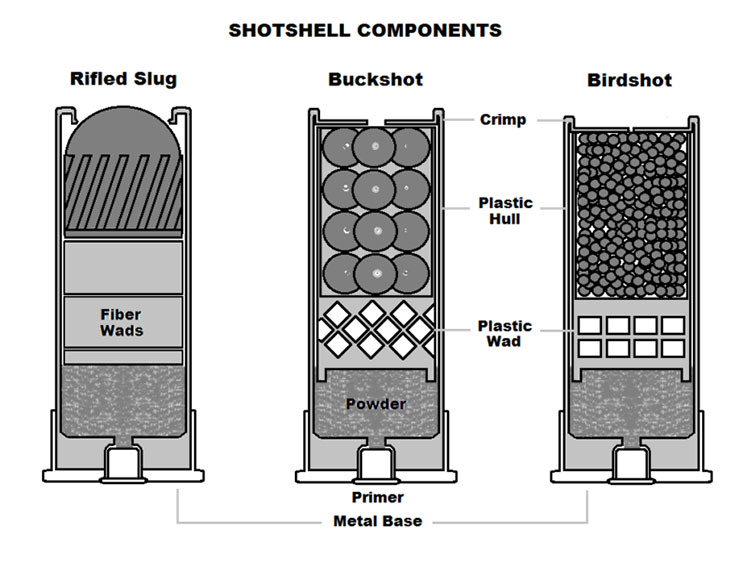

The metallic cartridges used in rifles and handguns fire bullets of various “calibers.” Shotguns fire multiple projectiles (shot pellets) through smooth-bore barrels that employ a “gauge” system. The interior diameter (bore) of a small rifled .22-caliber barrel will be much less than any number of today’s popular .30-caliber high-powered rifle options. But the shotgun’s “gauge” system is reversed.

The largest gauge sold today is the 10 gauge, a true heavy-hitter on both ends. Thus, the somewhat smaller but much more versatile 12 gauge is by far the most popular choice. The 16 gauge still exists, but it’s much less popular today because of improvements to the handier 20 gauge, which now occupies second place. The 28 gauge is smaller, and the .410-bore (not a true gauge) is the smallest. The latter two are also the most expensive to feed.

If ammunition prices are a concern, skip the .410 and consider whether shotgun reloading is worth your time. Also watch for ammo deals to buy in bulk when prices are down.

For most, the best all-around choice will be a 12 gauge, followed by the smaller 20. With either, 3-inch Magnum chambers are pretty much standard nowadays, although some 12s are even built to digest 3 ½” Magnums. Unless strongly into self-abuse, I’d plan on skipping the latter. Fortunately, these guns will also fire 2 ¾-inch shells. Truthfully, even the 3” loads can kick like mules, especially in lightweight single-shots. The few three-inch shells I shoot are reserved for turkeys and waterfowl, using softer-shooting autoloaders.

Useful Loads

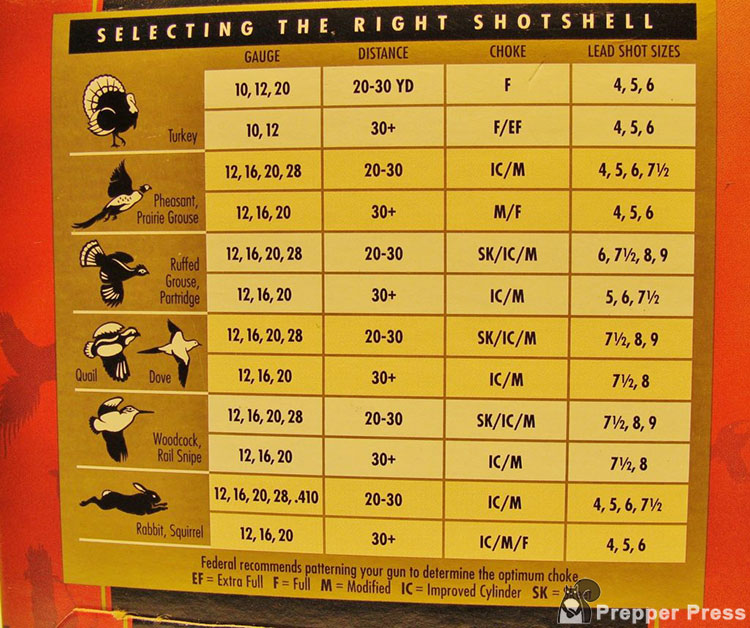

First, let’s take a quick look at shotgun pellets, which come in various sizes from tiny #9s to much larger #2s and BBs. The latter are best for geese, fox, or coyotes, etc. The largest buckshot pellets are for deer or defense. Those in between, from #6 – #4, are popular for game birds and small game. These loads will work out to 40 yards or thereabout.

A general-purpose choice might be a basic 2 ¾” pheasant load containing #6 shot, which can also handle mid-sized varmints like woodchucks or coons. Waterfowl will require a switch to non-toxic shells with steel being the cheapest. To offset the decreased killing power of the lighter pellets, move up to #4s or #2s, confining shots to those inside 40 yards.

For those interested in absolute minimum recoil:

- Winchester’s 12 Ga. low-recoil/low noise shells perform like very light 20 gauge loads.

- Federal’s Metro-load will perform similarly.

Either can dissuade marauding birds or be used to harvest quail and doves.

These light # 8 – # 7 ½ loads are also lots of fun to shoot during informal clay-bird sessions. They’re a great choice for younger beginners, too. There are other ways to reduce to shotgun recoil as well – if that’s a concern.

For many years, 12 gauge 2 ¾”, 9-pellet 00 Buckshot shells have been the choice for larger critters, or for defense. The premium loads will be effective out to 35-40 yards on quarry like hogs or deer. As it turns out, buckshot often patterns best in modified-choke barrels, fairly common among inexpensive break-barrels. You can preserve 20 gauge pattern density by switching to smaller buckshot pellets.

(L-R) General-purpose #6 shot, 00 Buckshot, and a rifled slug.

Rifled slugs are another possibility for use on the largest animals, including bears. The basic 12 gauge shotgun slug is essentially a big .73-caliber lead bullet that strikes like Thor’s hammer at close range. They’ll shoot reasonably well through chokes up “modified”, but accuracy will be iffy without decent sights.

Most basic break-barrel guns have 26 – 28” barrels with simple bead-type front sights, designed for pointing instead of aiming; perfect for placement of shot patterns on moving targets. A purpose-built “slug barrel” with rifle sights will easily cover 75 yards. Still, a basic bead may get the job done with slugs out to thirty paces or so.

Chokes and Patterns

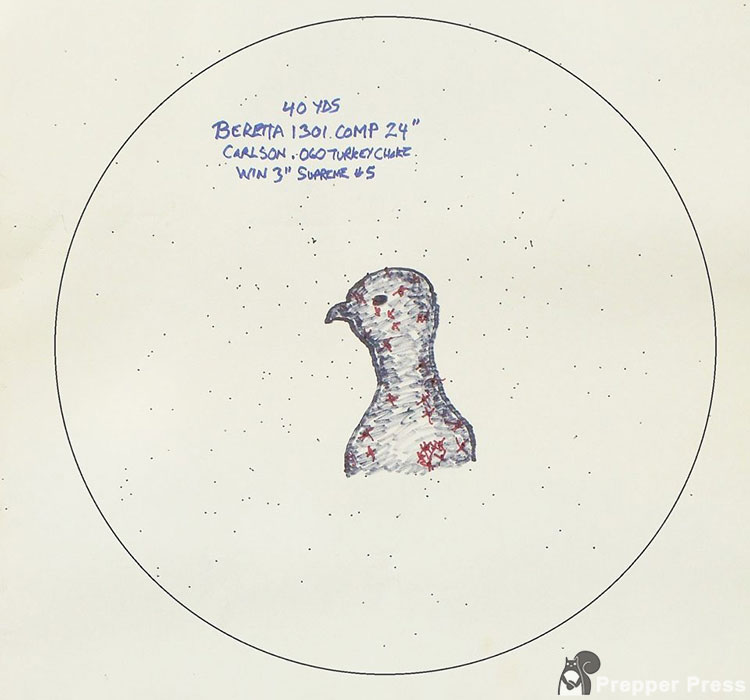

The term “choke” refers to a small degree of barrel constriction adjacent to the muzzle. This squeeze can concentrate an expanding pattern of shot into a smaller area, for use at greater ranges. But, tighter patterns aren’t always better.

The covey of bobwhites that explodes from your feet will present small and challenging targets. They’ll be much harder to hit with tighter chokes, and those that are could be shredded. Rather than hunt with tighter modified or full chokes, most folks would be better off with an improved cylinder.

The old standards from open-to-tight are improved-cylinder (IC), modified (mod), and full-choke, with constrictions averaging around .012”, .018”, and .035” for a 12 Ga. with a standard .729” bore. A cylinder-bore has no choke at all. Its business end should measure the same .729; an impressive .73-caliber!

The percentage of a shot pattern that strikes within a 30-inch circle at 40 yards will provide a truer indication of the choke, with a “full” being tightest at 70% or more. “Modified” will be around 60%, and IC will run around 50%; again, better for closer-range targets where more open patterns can increase hit probability.

Starting with a cylinder-bore 12 Ga. at 25 yards, you could expect to add about five useful yards per each extra degree of constriction, winding up at around 40 yards with full choke. But, these figures aren’t set in stone. The shells also play key roles.

By federal law, waterfowl must be hunted with approved non-toxics that substitute lead for steel, bismuth, or tungsten pellets. Being harder, they suffer less deformation, resulting in tighter patterns. Conversely, bargain lead shotshells with softer pellets could throw wider patterns.

What does this mean for the user? Well, for waterfowlers, a Modified choke will probably pattern closer to Full. In fact, many non-toxic pellets are hard enough to damage tighter chokes. Except, maybe, for Bismuth loads, I’d skip ‘em in older guns.

Until the 1970s most chokes were just swaged constrictions to the barrel. The advent of threaded, interchangeable choke-tubes greatly increased versatility, but inexpensive guns sometimes employ fixed-chokes (often Modified) simply to keep a lid on cost. But, here’s a trick; you can sometimes gain more open patterns by shooting cheaper shells.

Smaller Gauges?

As for the small .410, choices are either 2 ½” or more potent 3-inch types. However, neither holds many pellets, making effective shooting difficult. People treat the .410 as a beginner’s gun but it’s really more of an expert’s choice for this reason.

Comparing the ½-ounce payload of a 2 ½” .410 to a “light” 1 1/8-ounce 12 gauge, or a 7/8 oz 20 gauge shell, illustrates the reason. The 28 gauge falls between the .410 and 20, but as previously mentioned, shells are scarcer and much more expensive.

Shotguns for Homesteads Conclusion

For most folks a 12 or 20 gauge gun is by far the better all-around choice for a homestead, and a single-shot fits the bill affordably. A basic break-barrel single-shot may not be too glamourous, but it’ll probably cover most homestead duties. It’s also a low-maintenance acquisition that isn’t fussy about its diet. Just pop it open and drop in a shell. You can also tell at a glance if it’s loaded or empty.

But it does have an Achilles Heel – only one shot, which compromises its defensive capability. This is why I have not labeled single-shot shotguns as the single best shotgun for a homestead.

For a bit more cost though there are other good shotgun picks. The right choice will effectively cover everything mentioned above, along with one more critical role – an effective means for defense of home and hearth.

Want to learn more about shotguns? Steve Markwith is also the author of Shotguns: A Comprehensive Guide.

- Markwith, Steve (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

4 comments

This was an awesome explanation

I think you are a little off on your muzzle end bore diamenters. I would hate to try to shoot 12 .310 diamenter balls out of a .012 muzzle. lol

Thanks. What section are you talking about? Can you quote it?

Don’t forget you can utilize a simple technique called a “cut shell” to hunt for larger animals with a shell typically used for clay pigeons.