Seems like there is a fair share of confusion exists regarding shotgun gauges and shotgun vernacular in general, even among experienced shooters. I first picked up on this during an era when “scatterguns” were the deal-sealing choice of law enforcement. Those who attended my agency’s high-speed combat shotgun program arrived with extensive handgun backgrounds, and many were well versed in rifles.

However, the shotgun was rife with mysteries to include projectiles, various load options and often, even “gauges.” The entire topic is a full enough plate to dish out through a separate post. Meanwhile, especially for those with interest in procuring a highly versatile firearm, the shotgun’s “gauge” system provides a logical starting point.

The Gauge System

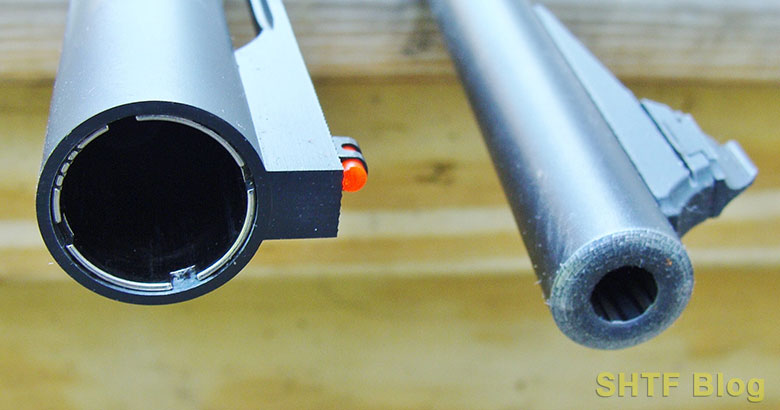

The conversation begins with the difference between a rifle (or handgun), and “smoothbore” shotgun. Rifles are designed to fire single projectiles dependent on precise barrel engagement and gyroscopic stability to prevent the erratic effects of bullet tumbling. The bullet’s nose-forward flight is maintained through “rifling”; a series of spiral grooves cut into the bore’s surface that correspond with the diameter of the bullet – its “caliber.”

Since a caliber equals one hundredth of an inch, by U.S. standards, a true .50-caliber barrel, measured groove-to-groove, would run a half-inch. A more familiar example, the .223 Remington, actually fires .224-caliber bullets. Per NATO and/or European metric standards, the same “caliber” is 5.56 mm.

The need to “gauge” projectiles to their barrels predates rifling, and the smoothbore system was based on weight. Nowadays a quarter-pounder equals a substantial dose of cholesterol, but in years gone by, an energetic shoulder-fired example provided a means to passive ponderous pachyderms – for those with the fortitude to endure its Newtonian effects.

In spherical form its lead projectile, if “gauged” to slip through the bore, would weigh 4-ounces. At four-to-the-pound, per the British “Gauge“ system, it would thus be classified as a four-bore – or 4-Gauge. The “smaller” but still formidable 8-bore was the upper limit for most shooters.

Thankfully, these massive spheres eventually gave way to lighter large-caliber bullets, stabilized by rifled barrels. But the gauge system endured for smoothbore shotgun barrels intended to shoot multiple projectiles known as “shot” pellets.

A much more tractable example is the semi-obsolete 16 Gauge, which still offers a nice balance of payload vs recoil in an appropriately sized shotgun (it’s possible to reduce shotgun recoil). Each lead ball, if sized to its bore diameter, should weigh 1-ounce. Simple math indicates 16 to the pound, its gauge. Today’s more popular 12 gauge has a larger bore which, in theory, should require only twelve, weighing 1 1/8-ounces apiece.

The weights of these spheres also approximate their standard shot payloads. However, particularly in respect to the ever-popular 12 Gauge, numerous load options are available above or below that weight. Also, the entire gauging process has always been “approximate.” Today’s shotgun barrels are produced on modern machinery to dimensional specs, but again, particularly regarding the 12 Ga., considerable dimensional latitude exists. More on this shortly.

Gauges, Past and Present

It’s possible to encounter shotguns in a large variety of gauges, from the above behemoth 4-bores to tiny 36 Ga. guns. But today’s options have evolved to a shorter and more practical list. Present offerings, from large-to-small, include 10, 12, 16, 20, and 28 Gauge, along with the .410-bore (which is actually a caliber approximating a 68 Ga.).

Occasionally, small-bore shells appear from offshore sources in obscure gauges like the 24 and 32 Ga., and the mighty 8 Ga. is still produced domestically as a specialized industrial load.

Among today’s common picks, the 10 Ga. is the viable upper limit, not only due to recoil, but also because it constitutes the federal maximum allowed for migratory waterfowl. Sales spiked once non-toxic shot became a waterfowling requirement but, of late, they’ve decreased due to a more potent version of the hugely popular 12 Gauge.

Along a similar vein, earlier on, the introduction of magnum-ized 20 Gauge loads eventually eroded 16 Ga. sales. Likewise, although the excellent 28 Gauge is still available, most of today’s shooters are probably more familiar with the .410; another load that eventually appeared as a “magnum” version.

Standard vs Magnum Loads

Like today’s gauges, their now standard and magnum loads are evolutions of earlier shell configurations. The length of a standard 12, 16, 20, and 28-Gauge shell is now 2 ¾-inches. Such loads nicely cover most shotgun chores from claybirds through small game and upland birds, as well as defense.

If waterfowl and turkeys make the list, longer and more powerful 3-inch magnum versions are available for all, except the 16 Gauge. As noted above, the 12 Ga. even includes a recent 3 ½” Super-magnum, marketed to compete with 10 Gauge.

At the small end of the spectrum, a standard.410 shell is 2 ½”. The 3” Magnum evolution boosted its skimpy ½-ounce shot charge to 11/16-ounces – close to the longstanding ¾ oz. payload of 28-gauge shells. But the lithe 28 Ga. recently received a boost via a 3” Magnum, which fires payloads exceeding the 20’s standard 7/8 oz. shot-charges.

More About Shell Lengths

The latest rage is ultra-short 12 Ga. Mini-shells, designed to boost the capacity of tubular pump-gun magazines – in guns capable of feeding them such as Mossberg’s 590 Series.

In their respective gauges, shorter shells (including the “minis”) can be safely fired through guns with magnum-length chambers. But not in reverse!

And even today’s standard-length shells may not be safe all guns. Many older shotguns were chambered to fire shorter (and often milder) shells of 2 ½” – or less. Thus, some that accept a modern shell could produce unpleasant consequences. Regarding the reference to “shells,” early black powder shotgun cartridges (circa late-1800s) often featured brass cases sealed by cardboard wads. But, even after the switch to more efficient smokeless powders, pressures remained low enough to work with so-called paper “shotgun shells” that were reinforced by metal bases.

The late 1960s saw the development of today’s plastic versions and, by that point, hulls of either material were sealed by crimping their mouths – which requires sufficient chamber space to accommodate the expanded petals. For this reason, a loaded 2 ¾” shell is usually shorter than 2 ½” – a potential problem in a short-chambered gun. If in doubt, measure the shell by its fired length.

Similarly, an unfired 3” Magnum will probably fit in a 2 ¾” chamber, but that doesn’t mean it’s safe to shoot. Far from it! If the crimp petals can’t fully open, pressure will immediately spike to unsafe levels. Today’s shotgun barrels are stamped with their gauge and chamber lengths, but even among those that can interchange, a 3-inch Magnum version may not be safe for a 2 ¾” receiver. If in doubt, play it safe and consult a gunsmith.

Related Gauge Details

Because the 12 Gauge is enormously popular it’s been a subject of extensive tinkering, to include lengthened forcing cones and back boring. Lengthened forcing cones provide a more gradual transition of the shot charge to the barrel. In theory, the funnel effect will soften recoil, with possible improvements to pattern uniformity.

If the funnel is extended far enough to increase the diameter of the barrel, it’s been back bored. The additional bore volume is purported to improve shot patterning via “squarer loads” (shorter shot columns) that reduce pellet deformation resulting from barrel contact.

Industry Specs & Tolerances

Manufacturers may also produce shotgun barrels to differing specs. A true lead 12 Gauge ball should measure .729” (about 73-caliber), but the U.S. industry standard (per SAAMI) allows .020” of leeway. Some recent iterations could be closer to 11-gauge – again, to provide more uniform patterns.

Most of the several dozen Remington Model 870s in our inventory measured close to .729”, but some were .732ish. Remington’s latest 3 ½” semiauto Versa Max is closer to .737”, and Mossberg advertises their 3 ½” Model 835 with “10-Ga. dimensions” of around .775”! These over-bored barrels provide more volume for vast quantities of hard non-toxic (or lead) pellets that can double the weight of a 2 ¾” target load.

The European 12 Ga. standard is .725”. My 3” Beretta Mobile Choke barrels average a tighter .723”, supposedly, to improve gas-sealing across a broad spectrum of global shells. A 12 Ga. Optima HP version on hand mikes .728”, while Beretta’s prior Optima barrels run around .732”. But, like U.S. built guns, some offshore makes are more capacious. Regardless of their origins, most advertised as “back-bored” are really just over-bored versions.

A potential hazard for larger bores: Some could produce underpowered “bloopers” with stiffer wads and/or light loads in cold weather. Cease fire and check for an obstruction if the report sounds iffy.

Choke Tubes

None of this will matter much to the average shotgunner. However, the installation of an incompatible choke tube could cause problems. “Choke” – the constriction of the barrel near the muzzle – is applied to regulate the dispersion of a shot pattern. Older guns have fixed built-in chokes but, today, interchangeable choke tubes are the norm.

Exact fit is essential since the choke’s skirt must seat below the surface of the bore. Because they’re manufactured to proprietary specs, if in doubt regarding fit, consult the internet for listings of suitable combinations.

Shotgun Slugs

Most shotguns are smoothbores, designed to fire shot pellets, but some are enlisted to shoot solid projectiles (slugs) that are capable of useful accuracy at closer ranges. In my experience, safety-wise, common Foster-type slugs (large, soft-lead bullets), aren’t overly fussy regarding bore diameters, – which makes sense since some could be fired through choke-constrictions as tight as “full”.

Still, expect better accuracy from plain-vanilla slugs using barrels closer to .729”. We fired tons of ‘em (literally) through dozens of LE M-870 pumps (improved-cylinder), and 3-inch groups at 50-yards were the norm. But Mossberg explicitly warns against the use of any solid projectiles in their cavernous M-835 barrels.

Choosing the Best Gauge for You

Most of the above info centers on 12 Ga. guns, simply because they represent the lion’s share of recent developments. If you’re after a basic shotgun, it’s more a matter of selecting a suitable model in the most practical gauge. Exotic calibers and gauges may be cool, but with ammo in short supply, a gun that can digest pretty much anything offers tangible benefits.

General Purpose Picks

To maximize versatility without breaking the bank, it’s hard to wrong with a fairly basic 12- or 20-Gauge shotgun. Ammunition for either is widely distributed in a broad range of load options that also keep a lid on ammo cost. See my article on the best shotgun for homesteaders.

A couple of guns that fit the bill are Remington’s Model 870 pumps, and the several similar versions sold by Mossberg.

Because both have been produced by the millions for decades, parts and accessories are readily available. I’d skip a 3 ½” 12 Ga. in favor of a 3” model. Although either will also fire 2 ¾” shells, a 3” version opens the floodgates to quick-change barrels covering all bases from big game (slugs) to defense.

Today’s 26-28” sporting versions, sold with interchangeable choke tubes, provide a useful foundation for extra barrels in shorter lengths, to include rifle-sighted slug versions. See my article on converting a Remington 870 into a Tactical Shotgun.

If recoil and/or weight are issues, consider a 3” 20 Gauge version. In either gauge, most of us will shoot far more 2 ¾” loads anyway, simply because they cover most needs for lower costs with less recoil. To further reduce recoil, try a gas-operated semiauto. Big difference!

Niche Picks

The 10 Gauge is more gun than most of will ever need. The 16 Gauge has enjoyed a trendy resurgence, but those built on 12 Ga. frames (many) negate its perceived advantages. Load options are also limited, and more costly.

Same story regarding the 28 Gauge; a neat boutique choice – if built on a properly scaled frame. If not, it’ll probably be built on a 20 Ga. that offers cheaper shooting.

Some people pick .410s as starter guns for kids. They’ll work at closer ranges for small game but, for wingshooting, the tiny shot charges really relegate them expert’s tools. Considering the price of shells, the more practical alternative could be a properly size 20 Ga., loaded with “low recoil” shells.

Or, with a supply of fired shells, you could even load your own. Read whether reloading shotgun shells is worth it or not.

Closing Comments – With a Caution

The takeaway: Unlike calibers, higher numbers translate to smaller bores. Thus, a 16 Ga. is approximately .66-caliber, a 20 Ga is about .62-caliber, and a 28 Ga. runs around .55-caliber – still much larger than a .410, the greatest step downward of the bunch.

As noted above, because they headspace on their rims, shorter shells of the same gauge can be fired. But a gauge mix-up can spell disaster. Drop a 20 Ga. shell in a 12 Ga. chamber and it’ll disappear. But its rim will hang up on the chamber’s forward end as a catastrophic bore obstruction.

Fortunately, most of today shells are color-coded, with yellow reserved for the 20 gauge. But, factoring in Murphy’s Law, it’s still worth any sanitizing vests or shell bags when switching to a different gauge.

Finally, for more about the fascinating world of shotguns, here’s a link to my book, Shotguns: A Comprehensive Guide:

- Markwith, Steve (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

2 comments

Excellent article. It is good to have such “Barney Fife” instruction presented as there are always newcomers to handling firearms.

This is a great read. I have a 20ga Mossberg with an adjustable choke (model 185k) . Most people have never heard of an adjustable choke much less one that is permanantly fixed! Clockwise/counter clockwise…